The 50-Year Evolution of AML Laws That Shaped Modern US Financial Compliance

In 1970, a bank teller in Manhattan accepts a paper bag containing $50,000 in cash from a well-dressed customer. For criminals looking to launder money through the U.S. financial system, it was the golden age.

In 1970, a bank teller in Manhattan accepts a paper bag containing $50,000 in cash from a well-dressed customer. No questions asked. No forms filed. No eyebrows raised. This wasn't just common practice—it was perfectly legal. For criminals looking to launder money through the U.S. financial system, it was the golden age.

Today, such a transaction would trigger multiple automated alerts, require extensive documentation, and potentially lead to a suspicious activity report being filed with federal authorities. The stark contrast between then and now tells the story of how American financial regulation evolved from a system built on trust to one designed around transparency and accountability.

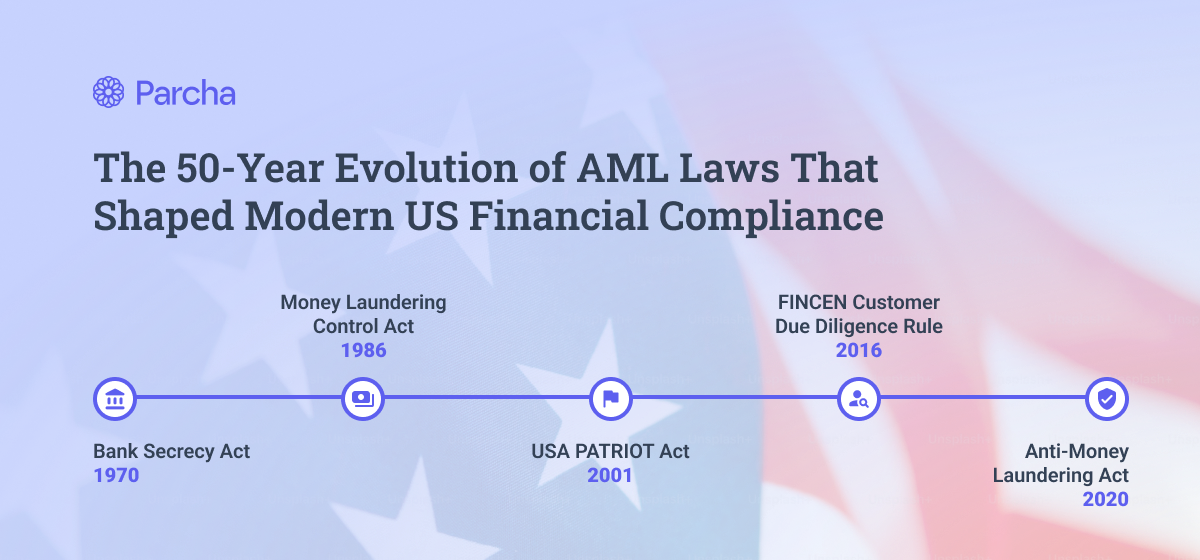

This transformation didn't happen overnight. It took five landmark pieces of legislation over fifty years to create the modern anti-money laundering (AML) framework we know today. Each law was a response to specific threats and challenges of its time, from the drug trade of the 1970s to the terrorist attacks of 2001 to the cryptocurrency boom of the 2020s.

The Origin Story

Bank Secrecy Act of 1970

When Congress passed the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) in 1970, it represented a fundamental shift in how America approached financial crime. For the first time, financial institutions were drafted into the fight against criminal activity. The concept was revolutionary: banks would serve as the first line of defense against money laundering by creating a "paper trail" of suspicious financial activity.

Enacted: October 26, 1970

Purpose: Assist U.S. government agencies in detecting and preventing money laundering

Key Provisions: Includes keeping records of cash purchases, filing reports for daily aggregate over $10,000, and reporting suspicious activities

The Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) of 1970, also known as the Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act, was a groundbreaking piece of legislation that laid the foundation for modern anti-money laundering efforts in the United States. This act was primarily designed to prevent financial institutions from being used as tools by criminals to hide or launder their ill-gotten gains.

Key provisions of the Bank Secrecy Act include:

- Requiring financial institutions to keep records of cash purchases of negotiable instruments

- Mandating the reporting of daily cash transactions exceeding $10,000

- Obligating financial institutions to report suspicious activity that might signify money laundering, tax evasion, or other criminal activities

The BSA introduced the concept of a "paper trail" for large currency transactions, which has become crucial for law enforcement agencies in tracking the movement of illicit funds. This requirement was a significant shift in the financial industry, as it placed the onus on banks and other financial institutions to actively participate in the detection and prevention of financial crimes. One of the most important tools created by the BSA is the Currency Transaction Report (CTR). Financial institutions must file a CTR for any cash transaction over $10,000, providing valuable information to law enforcement agencies about large money movements1. This requirement has been instrumental in identifying potential money laundering activities and other financial crimes.

The Act also gave regulatory and enforcement responsibilities to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), a bureau of the U.S. Department of the Treasury1. FinCEN plays a crucial role in collecting, analyzing, and disseminating financial intelligence to combat money laundering and other financial crimes.

While the Bank Secrecy Act was a significant step forward in combating financial crimes, it was not without controversy. Some critics argued that the act infringed on privacy rights and placed an undue burden on financial institutions.

The BSA also had a significant limitation: while it required banks to report suspicious activity, it didn't make money laundering itself illegal. This created an odd situation where the act of hiding illegally obtained money wasn't technically a crime, even though banks were required to report it. This gap would take another 16 years to close.

Making Money Laundering a Crime

The Money Laundering Control Act of 1986

By the mid-1980s, the cocaine epidemic was at its height, and drug cartels were moving billions through the U.S. financial system. The limitations of the BSA had become painfully clear. Enter the Money Laundering Control Act of 1986, which finally made money laundering itself a federal crime.

Enacted: October 27, 1986

Purpose: Criminalized money laundering for the first time in the United States.

Key Provisions: Includes sections 18 U.S.C. § 1956 and 18 U.S.C. § 1957, targeting financial transactions with proceeds from specific crimes.

The Money Laundering Control Act enacted as part of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, introduced two new criminal offenses:

- 18 U.S.C. § 1956: Prohibiting financial transactions involving proceeds of "specified unlawful activities"

- 18 U.S.C. § 1957: Criminalizing monetary transactions in property derived from specified unlawful activities exceeding $10,0001

The Act expanded the government's ability to combat organized crime and drug trafficking by targeting the proceeds of these illegal activities. It also introduced civil and criminal forfeiture provisions for money laundering offenses, allowing authorities to seize assets connected to illicit financial 2.

Key provisions of the Money Laundering Control Act include:

- Criminalizing the knowing participation in financial transactions involving proceeds of illegal activities

- Prohibiting the structuring of transactions to evade Currency Transaction Report (CTR) filings3

- Authorizing the use of wiretaps in money laundering investigations4

- Establishing a "sting provision" allowing for prosecution even when the funds involved were not actually derived from specified unlawful activities5

The Act's scope extended beyond traditional financial institutions, applying to individuals and businesses engaged in or attempting to engage in prohibited financial transactions6. This broader application significantly enhanced the government's ability to prosecute those laundering criminal proceeds.

The Act's impact was far-reaching. By criminalizing money laundering itself, it fundamentally changed how banks approached compliance. With both civil and criminal penalties now possible, financial institutions began investing more heavily in compliance programs to protect themselves from liability.

Post-9/11 Transformation

The USA PATRIOT Act of 2001

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, exposed critical vulnerabilities in the U.S. financial system. The response was swift and comprehensive: Title III of the USA PATRIOT Act, known as the International Money Laundering Abatement and Anti-Terrorist Financing Act.

Enacted: October 24, 2001

Purpose: Designed to enhance law enforcement investigatory tools and prevent terrorism

Key Provisions: Required financial institutions to report potential money laundering

Key provisions of the USA PATRIOT Act related to AML/CTF include:

- Enhanced Customer Identification Programs (CIP): Financial institutions were required to implement robust procedures to verify the identity of customers opening new accounts2.

- Increased Due Diligence: Banks were mandated to conduct enhanced due diligence on foreign correspondent accounts and private banking accounts for non-U.S. persons1.

- Prohibition on Shell Banks: The Act prohibited U.S. financial institutions from maintaining correspondent accounts with foreign shell banks2.

- Information Sharing: Section 314(a) established a mechanism for law enforcement agencies to request information from financial institutions about individuals suspected of terrorist activities or money laundering1.

- Expanded Definition of Financial Institutions: The Act broadened the scope of entities subject to AML regulations, including money services businesses, credit unions, and securities brokers2.

- Special Measures: The Treasury Department was granted authority to impose additional regulatory requirements on financial institutions or jurisdictions posing money laundering concerns1.

- Increased Penalties: The Act significantly increased civil and criminal penalties for money laundering and related financial crimes2.

The USA PATRIOT Act also expanded the role of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) in coordinating and analyzing financial intelligence to combat terrorist financing1. This legislation marked a pivotal shift in the AML landscape, emphasizing a risk-based approach to compliance and fostering greater cooperation between financial institutions and law enforcement agencies.

The PATRIOT Act marked a fundamental shift in how financial institutions approached customer relationships. No longer was it enough to simply monitor transactions - banks now had to know exactly who they were doing business with. This "know your customer" mandate created ripple effects throughout the financial system, leading to more stringent onboarding procedures and enhanced due diligence requirements, particularly for foreign accounts.

Yet as financial institutions implemented these new requirements, a crucial gap remained: while banks were required to identify their customers, there was no standardized approach to understanding who actually owned or controlled the legal entities they were serving. Criminal organizations and terror networks could still hide behind complex corporate structures. It would take another fifteen years before regulators addressed this vulnerability.

The Push for Transparency

FinCEN Customer Due Diligence Rule of 2016

By 2016, financial technology was transforming how people moved and managed money. Mobile banking, peer-to-peer payments, and digital wallets were making financial services more accessible than ever. But this convenience came with risk: the easier it became to move money, the easier it became to hide its true ownership.

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) responded with the Customer Due Diligence (CDD) Rule. Taking effect in 2018, the rule aimed to provide consistent standards for how financial institutions identify and verify their customers. Most crucially, it addressed a critical vulnerability in the U.S. financial system: the lack of transparency around beneficial ownership of legal entities.

Enacted: May 11, 2018

Purpose: Clarify and strengthen customer due diligence requirements.

Provisions: Required financial institutions to report potential money laundering

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) Customer Due Diligence (CDD) Rule, implemented in 2016 and effective from May 11, 2018, marked a significant enhancement in the United States' anti-money laundering (AML) framework. This rule clarified and strengthened customer due diligence requirements for covered financial institutions, including banks, brokers or dealers in securities, mutual funds, and futures commission merchants and introducing brokers in commodities1.

The CDD Rule introduced four core elements:

- Customer Identification and Verification: Covered financial institutions must identify and verify the identity of customers.

- Beneficial Ownership Identification and Verification: Financial institutions are required to identify and verify the beneficial owners of legal entity customers2.

- Understanding the Nature and Purpose of Customer Relationships: Institutions must understand the nature and purpose of customer relationships to develop customer risk profiles.

- Ongoing Monitoring: Continuous monitoring of customer relationships is mandated to identify and report suspicious transactions and maintain and update customer 3.

The CDD Rule represented a crucial evolution in how financial institutions approach customer relationships. For the first time, banks were required to identify and verify the beneficial owners of legal entity customers - specifically, any individual who owns 25% or more of a legal entity, and one individual who controls the entity.

This was more than just an additional compliance requirement. It represented a philosophical shift in how regulators viewed financial crime prevention. The focus moved from simply identifying suspicious transactions to understanding the people behind them. This change acknowledged a simple truth: criminals and terrorists don't typically open accounts in their own names.

The Modern Framework

Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020

As we entered the 2020s, the financial landscape had changed dramatically. Cryptocurrency was emerging as a new frontier for financial crime, cyber threats were growing more sophisticated, and the global nature of financial crime required unprecedented international cooperation.

Enacted: January 1, 2020

Purpose: to strengthen, streamline, and modernize AML and counter-terrorism financing (CFT) laws.

Provisions: Centralized benifial ownership register, expanded BSA/AML scope to crypto, enhanced penalties.

The Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA) of 2020 represents a significant overhaul of the U.S. anti-money laundering (AML) regime, building upon and modernizing the existing framework established by the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). Enacted as part of the National Defense Authorization Act, the AMLA aims to strengthen, streamline, and modernize AML and counter-terrorism financing (CFT) laws12.

Key provisions of the AMLA include:

- Beneficial Ownership Registry: The Act mandates the creation of a centralized beneficial ownership registry maintained by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). This registry aims to enhance transparency and combat the use of shell companies for illicit purposes3.

- Expanded BSA/AML Scope: The AMLA broadens the definition of "financial institution" to include businesses dealing with virtual currencies, thus expanding regulatory oversight to the cryptocurrency sector1.

- Whistleblower Program: The Act establishes a robust whistleblower program, offering increased protections and incentives for individuals who report BSA violations4.

- Enhanced Penalties: The AMLA significantly increases civil and criminal penalties for BSA/AML violations, including the possibility of clawing back bonuses from executives of repeat offenders1.

- Focus on Innovation: The Act promotes the adoption of new technologies in AML efforts, encouraging financial institutions to implement innovative approaches to compliance2.

- Information Sharing: The AMLA enhances information-sharing capabilities between financial institutions, regulators, and law enforcement agencies1.

- AML/CFT Priorities: The Act requires FinCEN to establish and periodically update national AML and CFT priorities, which financial institutions must incorporate into their compliance programs5.

- Expanded Subpoena Powers: The AMLA grants the Department of Justice and Treasury expanded subpoena powers over foreign banks maintaining correspondent accounts in the U.S.1.

The AMLA represented the most comprehensive reform of AML laws since the PATRIOT Act. Perhaps most significantly, it created a centralized beneficial ownership registry - addressing a longstanding weakness in the U.S. financial system. This marked a shift from putting the burden solely on financial institutions to creating a national framework for entity transparency.

Looking Forward

The Next Evolution of AML

Today, we're witnessing the next transformation in AML compliance as artificial intelligence and machine learning reshape how institutions detect and prevent financial crime. The paper trails of the 1970s have given way to sophisticated pattern recognition algorithms that can analyze millions of transactions in real-time.

Yet the fundamental principles established by these five landmark laws remain as relevant as ever. Each piece of legislation builds upon its predecessors, creating an increasingly sophisticated framework for preventing financial crime. From the BSA's basic reporting requirements to the AMLA's technology-embracing provisions, we can trace a clear evolution in how regulators and financial institutions approach this crucial mission.

For banking and fintech leaders, understanding this history isn't just academic - it provides crucial context for current requirements and insights into future trends. As new threats emerge and technology continues to evolve, we can expect further refinements to this framework. But its foundation, built over fifty years of legislative innovation, will likely continue to guide financial crime prevention efforts for decades to come.

The story of AML legislation is ultimately about adaptation - how regulators and financial institutions have continuously evolved to meet new challenges. As we look to the future, this capacity for adaptation will be more important than ever in maintaining the integrity of the global financial system.

If you need any help with navigating compliance for your bank or fintech, reach out to founders@parcha.ai.